This feature gives an accessible overview of a clinical issue of interest to all physio staff. David Head, chief executive of the Haemochromatosis Society, explains physiotherapist’s role in diagnosing this condition.

Haemochromatosis – What is it?

Genetic (or hereditary) Haemochromatosis (GH/HH) is also known as ‘iron overload disorder’.

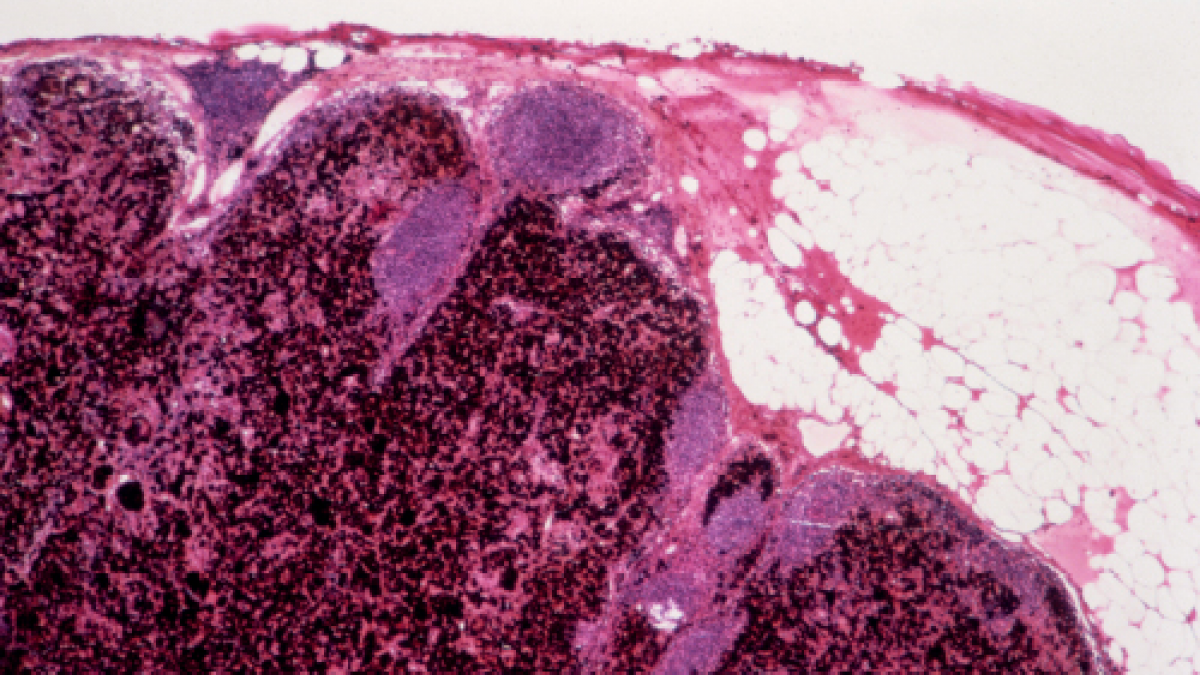

GH is mainly found in people of North European ancestry. It is a common inherited disorder that results in the absorption of too much iron from the diet. It is not possible to control this condition by diet and the excess iron builds up to toxic levels in organs such as the liver, heart, pancreas, pituitary gland and skin. In the worst-case scenario, high levels of iron can lead to fatal outcomes.

Early symptoms can include, but are not confined to, joint pain/stiffness, fatigue, and weakness especially in the hands, feet, hips, knees, ankles. In some cases it can also cause a skin discolouration due to deposition of the iron pigment haem. ‘Bronze diabetes’, a term originally used to describe the association of cirrhosis, diabetes and skin pigmentation, is a known complication of iron overload.

Early diagnosis is vital. Left untreated or diagnosed too late, people who express the clinical symptoms of GH have a higher rate of mortality than the general population, for example from liver cirrhosis, heart failure or hepatocellular cancer. But early detection and treatment in the pre-diabetic and pre-cirrhotic stages results in normal survival.

What is the physiotherapist’s role?

Much of the serious damage caused by GH is preventable by early diagnosis and de-ironing treatment and early detection is where physiotherapists have a role to play.

Research has shown a very high prevalence of joint symptoms in up to 80 per cent of GH patients. This is often one of the earliest symptoms and not uncommonly reported to have predated GH diagnosis by more than five years.

For the physiotherapist, joint symptoms resembling osteoarthritis (OA) should raise suspicion if reported in the absence of physical trauma, at an unexpectedly young age (sixth decade or earlier) and at unusual sites for OA, especially the metacarpophalangel (MCP) joints in the hands and the ankles or sub talar joints.

Physiotherapists noting such symptoms can draw a patient’s attention to the possibility of iron overload (GH) and can recommend that the patient ask their GP to run a simple blood test for ferritin and transferrin saturation that can show whether stored iron levels are abnormal.

How is the condition treated?

In most cases treatment is very straightforward, consisting of de-ironing by regular removal of blood by venesection (similar to blood donation). To replace lost blood, the body uses stored iron to make new red blood cells so reducing the stored iron to safe levels.

After diagnosis, the venesection process normally takes place under the direction of a consultant haematologist on a weekly basis (known as the de-ironing phase) until safe levels have been reached. Thereafter, the patient will need to have their ferritin levels monitored and will usually require two to four venesections a year for life to maintain safe stored iron levels. This is known as the maintenance phase. In the UK patients in maintenance can donate blood to the National Blood Transfusion Service, provided all other conditions of that service are met. Their iron and haemoglobin levels continue to be monitored by their consultant.

Does treatment prevent further joint pain and arthritis?

No. Joint damage cannot be reversed by de-ironing and further joint deterioration is often reported. However, early diagnosis and treatment can prevent excess iron damage to the major organs and endocrine system and patients who are diagnosed and de-ironed at an early stage can expect a normal life span. fl

- David Head is Chief Executive, The Haemochromatosis Society

Acknowledgement:

The Haemochromatosis Society wishes to acknowledges with grateful thanks the assistance of Dr Patrick Kiely, consultant rheumatologist at St George’s Hospital, London, without whose assistance this article would not have been possible.

Further information and publications are available from:

The Haemochromatosis Society, P.O. Box 6356, Rugby, CV21 9PA;

email: office@haemochromatosis.org.uk; website: www.haemochromatosis.org.uk;

Telephone: 03030 401 101

At-a-glance facts

- The gene flaws that can cause genetic haemochromatosis are believed to be carried by as many as one in eight people of northern European descent.

- Symptoms of iron overload can mimic those of iron deficiency (chronic fatigue), leading to non-diagnosis or being prescribed iron supplements.

- Impotence, loss of libido, early menopause, arthritis, depression, fatigue, hair loss, skin discolouration, mood swings and other symptoms can all be caused by iron overload.

- Haemochromatosis is a systemic problem affecting hormone production, liver function, brain function, joints, and more.

- GH causes cirrhosis of the liver and liver cancer; patients have been dismissed as ‘silent’ drinkers, GH not considered as a possibility by some consultants.

What should a physiotherapist look out for?

The arthritis that is most closely associated with haemochromatosis resembles osteoarthritis. However it is distinctive in occurring at a younger age and should be suspected where there is an absence of trauma and involvement of joints not normally associated with osteoarthritis – in particular the MCP, ankle, sub talar and mid foot, (tarsometatarsal) joints. It also affects other sites which are typically seen in OA, such as the hip, knee, proximal interphalangeal and first carpometacarpal joints, but the recognition of OA at unusual sites is more likely to be the clue to the diagnosis.

A physiotherapist, by advising a patient to request a simple blood test, could be helping an unsuspecting GP to make a diagnosis before the excess iron can cause permanent major organ damage.

You might even help save a patient’s life as a result.

Further reading

1) Haemochromatosis: unexplained metacarpophalangeal or ankle arthropathy should prompt diagnostic tests: findings from two UK observational cohort studies. A Richardson, A Prideaux, P Kiely Scand J Rheumatol 2016; 00:1-6.

2) Hereditary Haemochromatosis – The BMJ BMJ 2016; 353:i3128 published June 2016.

Author

David Head, chief executive of the Haemochromatosis SocietyNumber of subscribers: 3