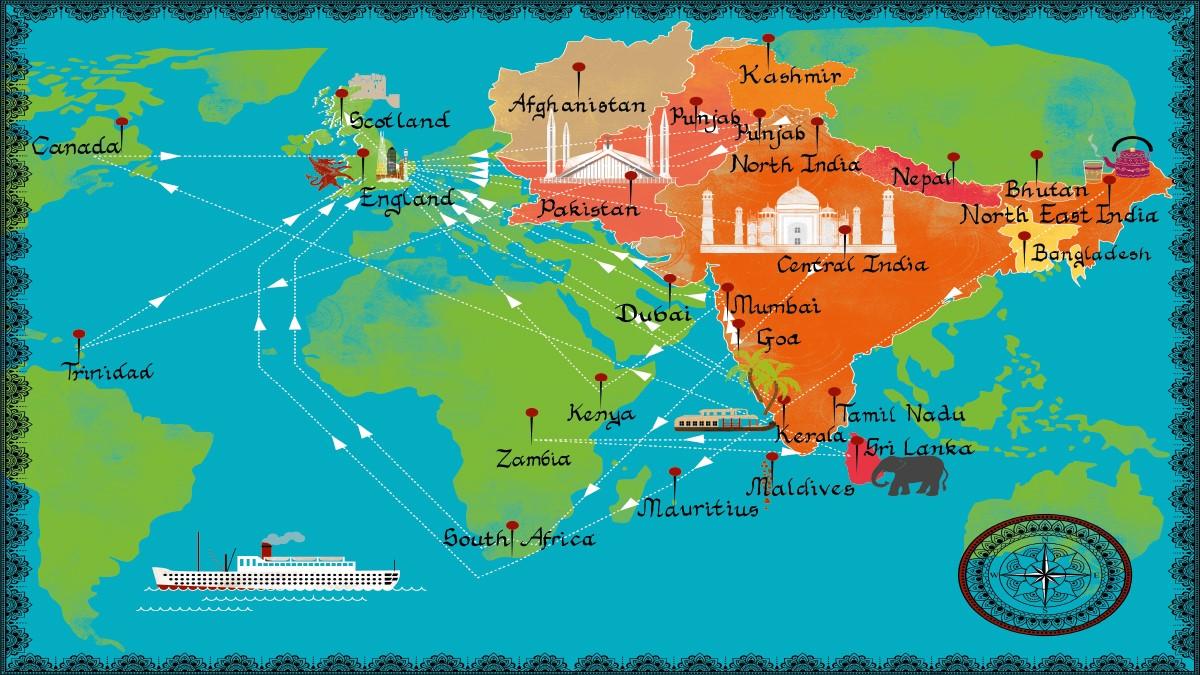

South Asian people have moved around the globe, learning from different cultures and workplaces before bringing that knowledge to UK healthcare. Radhika Holmström meets members from varied backgrounds, faiths and countries of ancestry

People from South Asia have been coming to the UK for hundreds of years – to work, study, train and generally enrich the population, whether they remained or returned. As a result, there’s also a growing proportion of people of mixed ethnic origin, who may identify with different elements of their heritages. Language, clothes, food and culture have all been influenced while industry, technology and, of course, healthcare have all gained hugely.

Within the UK population, the latest census has the Asian population of England and Wales at 7.5 per cent (in Scotland it’s lower at 2.7 per cent; and in Northern Ireland lower still). Yet there is a stereotype in the UK health service that it has a high proportion of South Asians; and there is some truth in that because around 10 per cent of the NHS workforce is Asian.

However, break down the figures and something odd emerges – more than 30 per cent of doctors are from this background while ‘non-medical’ staff, including nurses, of Asian origin make up only 8.7 per cent of the workforce.

And the figures within the physiotherapy profession are considerably lower; in fact, the CSP’s statistics show that only about one in 20 (5.43 per cent) are of Asian heritage. So why is the proportion relatively low among physiotherapy staff, and how have South Asian members found the experience of working in this field?

‘The first thing that Muslim patients ask is that I keep them in my prayers’

Muhammad Tai completed his physiotherapy degree during the pandemic, so for much of the time he has been staying in Batley in Yorkshire, where he grew up. ‘It’s a very Asian-British area,’ he says. ‘My whole street is full of Asian Muslim families, and in fact all through school I lived in this bubble. A lot of people from our community already work in the medical field, though none that I know are physiotherapists. Not many people know what my particular field involves, but they were quite open to the idea when I started explaining about the training and how hands-on and rigorous it was.’

Muhammad had personal reasons for training as a physiotherapist too, having accompanied his mother on rheumatology physiotherapy appointments. ‘It was a unique area to be exposed to and, in fact, that physiotherapist became my educator when I started training,’ he said.

It was when he went to college and university in Huddersfield that he started experiencing a different community. ‘I think the biggest change was also meeting older people, who were mature students or retraining; it really wasn’t what I had expected, and that was when my culture kicked in, because I was used to being respectful towards older people and now here I was studying with them.’ What he didn’t see was very many Asian students on his course. In fact, it’s only been in his third year placement that Muhammad met Asian colleagues with whom he could talk about practical issues such as combining work and fasting during Ramadan. ‘I was living two lives; as an imam leading the prayers every night, and then going in to be a physiotherapist during the day,’ he explains.

This was particularly important because Islam is a central element of his life. He undertook further Islamic studies every evening while at university – and this, in turn, adds to his professional practice, both with his colleagues and with his patients. ‘It’s good to be able to answer questions about the reality of the Quran and Islam. Most of the Asian patients I see are Muslim and the first thing they ask is that I keep them in my prayers. That’s the first thing that Muslims always ask of someone. So when they see me coming towards them, they recognise who I am – and it reassures them.’

‘It’s been a fascinating and very complicated journey’

The first time that Deepak Agnihotri saw a plane up close was in 2010, as he was boarding his flight from Delhi to London. He was on his way to the University of Salford to study for an MSc after growing up and training in Gwalior, central India, and then working in a major Mumbai hospital. ‘My passion was gait analysis and manual therapy, and when I looked into it, this was the university which was offering both.’

He missed his home and his family – he has flown back frequently since he arrived – but the biggest learning curve was the entire UK system. ‘I spoke English, but I didn’t know what people meant by a “weekend”, for instance.’

And that also meant learning about the health and social care system. ‘I was a qualified physiotherapist, but I didn’t know what a social worker or a care package was. I didn’t have the information about the NHS and how it functions. That’s the biggest issue that international students face, and it has been a fascinating and very complicated journey from student to advanced clinical practitioner.’

Even after his research was published in 2014, and he had worked as a funded research associate, securing his first post took Deepak some time. ‘Landing a job was a full-time job in itself. I’ve done hundreds of applications. I’ve travelled to places I’ve never heard of to do interviews. But the NHS is also the best organisation I’ve ever worked for and the most supportive. Of course it has its own flaws and challenges, but I’ve never looked back.’ And he found his own specialism – working with people with learning disabilities.

‘One of the things that struck me in the UK is that when you move into a field, you stay in that speciality. The beauty of working with learning disabilities is that I have patients with all kinds of conditions and that actually uses the full range of my own skills and experiences. I’m working with some beautiful people and it’s very rewarding to be able to make such a level of difference.’ In fact he has become the first advanced clinical practitioner learning disability physiotherapist in England.

‘My thoughts and feelings about my ethnicity and background have been much at the forefront of my thinking in the past couple of years. When I arrived, I was very naïve about diversity,’ he says. ‘I didn’t realise how being a vegetarian, a Hindu, an Indian, would be different in the UK. I’m now chair of the BAME network in my trust, and one of the 14 Black, Asian and minority ethnic strategic advisers to NHS England and Improvement. There’s still a long way to go. People don’t know what South Asian means, how diverse we are, what diversity is and how we can improve the patient experience.’

‘It’s better to live among people and learn to understand them’

One of the things that attracted Muhammad Mubeen to come to the UK was, he says, the diversity here. ‘I felt I’d mix with a lot of different cultures and people, compared to Lahore,’ he explains. ‘That was important to me. Most people have their own preconceptions about others; it’s better, I think, to spend time living among them and learning to understand them a bit more, rather than relying on assumptions.’ And so, 17 years ago, he left Pakistan where he had headed up a department in a 550-bed hospital and treated some of the most senior people in the country, and moved to restart his career from scratch.

He has certainly experienced that diversity for himself, moving around from place to place in the early stages of his UK career. ‘Just 100 miles from London was different to London. Norfolk, Stockton-on-Tees, Scotland; they’re different everywhere.’ And within that, he’s found differences in the way he is treated, as a Pakistani Muslim. ‘In Norfolk, people opened the windows to stare at me. In London, there’s a lot of different cultures and communities and I was very welcomed. Sheffield has halal shops and mosques, and Stockton-on-Tees had a very good Pakistani community too. When

I’ve moved house, Pakistani people and Pakistani taxi drivers have helped me. People are pleased and proud to have someone educated and qualified from Pakistan come to the UK.’

Having said that, Muhammad’s career in the UK has not all been plain sailing. ‘I’ve experienced racism and discrimination. That includes at work. But each time, the next place and the next job I moved to was better. It’s always possible to move on and to move up.’ He’s also faced a considerable range of assumptions about his religion and his appearance. ‘I am a Muslim. I’m from Pakistan. I pray five times a day; I’m practising. Not everyone understands or likes that, and that is also a big problem.’ He points, in particular, to physiotherapist Salman Afzal, who was also from Lahore and was killed in a racist attack in Canada earlier this year. ‘We should appreciate his work on Covid-19 and condemn his killing. People have their preconceptions about Asian people, especially Muslims with beards, until they start talking to us about our culture and religion. Sometimes you have to organise your work around your prayers, and others need to understand and respect that as well.’

Muhammad concludes:

We all need to be educated about each other, and about the different things that make up our worlds and our communities.

‘The higher up you get, the fewer of us there are’

Raakave Yoganathan only relatively recently discovered the physiotherapy profession, after a first degree, a master’s and a year’s experience working in psychology. ‘I was getting quite frustrated, I wanted to be able to achieve more and then I found I could be a rehab assistant,’ she explains. ‘I started in the middle of the pandemic; the team was under a huge amount of pressure and I walked in completely new, with no physiotherapy experience. But the hospital where I work is amazing in the support it gives you. I realised this was what I wanted to do for the rest of my life and I started investigating training and qualifying.’

Raakave’s parents were originally from Sri Lanka but met as refugees in Germany and lived in Munich before moving to the UK when she was 10. ‘London was very different, and ironically it was a culture shock to be suddenly in a Sri Lankan community, surrounded by other people who looked like me.’ In her new field, though, she is very aware of being back in a minority – and one major reason for this, she feels, is the lack of information and awareness about this career option. ‘I’ve been talking to colleagues from different physiotherapy departments about how going into physiotherapy wasn’t really something we’d been brought up to consider as a career choice. My parents were refugees who were working really hard to support us. They knew about the fields like doctors and lawyers, but they weren’t aware of AHPs, and my school didn’t equip us either with the information. I don’t think there’s enough seen about people of South Asian heritage who are working in this environment.’

As a new entrant into the profession, she has also been thinking about how this lack of visibility may affect her ability to move up. ‘We have conversations at work about the need for someone who understands and is in your corner rooting for you. Physiotherapists of South Asian background don’t have that many role models, and that also affects how you see yourself. There is such a small community still, even though it’s very supportive. It’s always notable that ethnic minorities struggle to get onto a higher level. And yes, it does concern me. Am I going to be able to move up in the same way as some of my colleagues? When I look around, the higher up you get, the fewer of us there are and it’ll probably be harder for me to break through.’

There’s always been a split between personal and professional space’

‘We talk a lot about how we build trust, as health care professionals, with minority ethnic patients and I think seeing someone who looks like you is actually quite powerful in building those relationships. I don’t necessarily give a different treatment: it’s just the issue of recognition and relating to someone,’ says Alicia Fernandez Butler, who’s a band 7 in critical care.

Alicia’s decision to study physiotherapy came from spending time in hospital as a child. ‘When we started talking about careers in secondary school I remembered just how much fun I’d had with the physiotherapists, and really from age 13 or so that was what I wanted to do.’ She grew up as part of the Goan community in inner city Leicester, in a very diverse area, but also attended predominantly white Catholic schools. ‘Home was very Goan; the locality, school, very white. It’s been similar since then. There’s always been that split between my workplace as a minority and my personal space where I am the norm.’

Today, Alicia lives in Croydon where the diversity is similar to that where she grew up. At work, though, it remains much the same. ‘I’ve been doing a lot of work leading equality and diversity work within the allied health professions (AHPs) in the hospital where I work. The most recent census data shows that in the wider area black, Asian and minority ethnic people make up 50 per cent; it’s the same for the wider workforce within the hospital; but within AHPs it’s less than 15 per cent.

That definitely didn’t surprise me. Once again, we’re a minority within a broader community.’

At the same time, that small group of Asian physiotherapists is also providing patients from the wider community with something enormously valuable. ‘It may be just being able to pronounce someone’s name properly, or ask them how they want to be addressed. I think there’s a lot of stereotyping about patients that professionals bring, and I do my best to communicate in a way they’ll understand.’ Alicia adds: ‘I’ve seen a lot of Asian patients suffering from Covid-19. It’s important to recognise that, and the impact of seeing a greater proportion of patients who look like you. It’s had a big effect over the past year.’

‘There’s still a lot of work to be done’

‘People might think it has always been easy for me, especially when they meet me at my consultant level,’ says Rashida Pickford. The reality, she explains, was rather different. When she first arrived in the UK from Mumbai, she had to get to grips with everything from the food, to the weather, to the structure of the NHS itself; and despite very welcoming colleagues in her first post, moving up from a band 5 post was not straightforward.

‘When I was applying for more senior roles and being rejected nobody was able to tell me what I wasn’t doing well. I assumed they did not trust me or my capabilities. I wondered if maybe I wasn’t good enough or qualified enough. It was a difficult time and a slog. There were times when I felt an interview had gone well, and the feedback didn’t tell me what I could have improved on. It was a little bit soul-destroying. It was nothing I could point my finger at, but I look back and allow myself to think about it properly, and hear similar stories from other people, I think quite strongly that ethnicity was an issue. You have to prove yourself, and push harder to climb up to more senior roles. And along the way, patients and colleagues tend to assume automatically that you’re not the person in charge, based on how you look.’

Today, Rashida is a consultant MSK physiotherapist working in a leading hospital. ‘I have now been in the UK for 30 years,

I’ve married an Englishman, and we have a home and family,’ she says. ‘But when someone says “home”, I always ask “which one?”. I have two homes now: my childhood home where my parents live and the new home with my husband and son.’ This, too, is something that peers who grew up in other countries may recognise. And that combination is important to her, because it brings her both personal and professional strengths.

‘There have been hardships which haven’t all been resolved,’ Rashida concludes. ‘Although we have a lot of awareness there is still a lot of work to be done. My advice to my younger self would have been: “don’t be afraid of being different, sounding different, approaching things in a different way. Don’t take away so much of your identity that you lose the unique perspective you bring to your work.” I want other people in my field to feel that they too can progress to consultant level. Don’t give up. Stick with it. The more diverse role models there are the more acceptance we have, the more normalised we are. And we are getting there.’

Number of subscribers: 1