Why getting good sleep is vital.

Sleep is important for health and wellbeing, and is the only single common risk factor associated with cardiovascular, metabolic, mental and physical health. Physiotherapists in all specialities manage various long-term conditions with coexisting insomnia and therefore this clinical update on sleep is written with clinical practice in mind. The update is presented in two parts. The first is an overview of sleep, prevalence of insomnia and its health risks. The second part (in Frontline 6 March issue) is an overview on the assessment and non-pharmacological management of sleep.

An overview of sleep

Sleep is generally defined as behavioural quietness, inactivity that is accompanied by closed eyes, a recumbent posture, limited muscular activity and reduced responsiveness to sensory stimulus. During sleep there is a decrease in muscular activity, heart and respiratory rate, blood pressure, blood levels of cortisol, adrenaline, and noradrenaline; and an increase in blood levels of the growth hormone, prolactin and melatonin (Besedovsky et al. 2012). Sleep has an important role in protein synthesis, cell growth and proliferation, memory and learning, metabolic, hormonal and appetite regulation (Lavigne et al 2007).

Within sleep there are two separate and distinct states: rapid eye movement (REM) and non-rapid eye movement (N-REM) sleep. N-REM is divided into four stages. Stages 1 and 2 are known as light sleep, while Stages 3 and 4 are referred to as deep sleep and considered to be the stages when the body and brain processes are restored or recuperating. In REM sleep, the brain activity is similar to that of a waking state. Every day N-REM alternates with REM and a healthy adult spends 80% of the average night in N-REM. The arousal threshold for waking up is low during stage 1 and at its highest in stage 4; i.e., it is easy to wake up in light sleep and difficult in deep sleep.

Economic burden of insomnia

As the criteria for insomnia have changed over the years, the estimates of prevalence of insomnia have also varied. Insomnia disorder prevalence rates in a cross-sectional study of 25,579 participants across the UK and Europe found 6.6 per cent met primary insomnia disorder criteria and 34.5 per cent reported at least one insomnia symptom. Insomnia symptoms occurring at least four nights per week are frequent in Sweden, affecting about 32.6 per cent of the population. Insomnia has significant direct and indirect health economic context. The direct cost is the utilisation of healthcare services and medication. The indirect costs are absenteeism and loss of production. As an example, Morin et al (2009) reported the total cost of insomnia for the province of Quebec is 6.6 billion Canadian dollars per year.

Sleep is a health risk factor

More than 40 per cent of individuals with insomnia, aged 15 years or older, from five European countries (the UK, Germany, Italy, Portugal and Spain) reported at least one chronic painful physical condition associated with difficulty initiating, or inability to resume, sleep once awake and a shorter sleep duration (Ohayon MM, 2005). It is estimated that 50-90 per cent of chronic pain patients and 30-50 per cent of cancer patients report severe sleep disturbance.

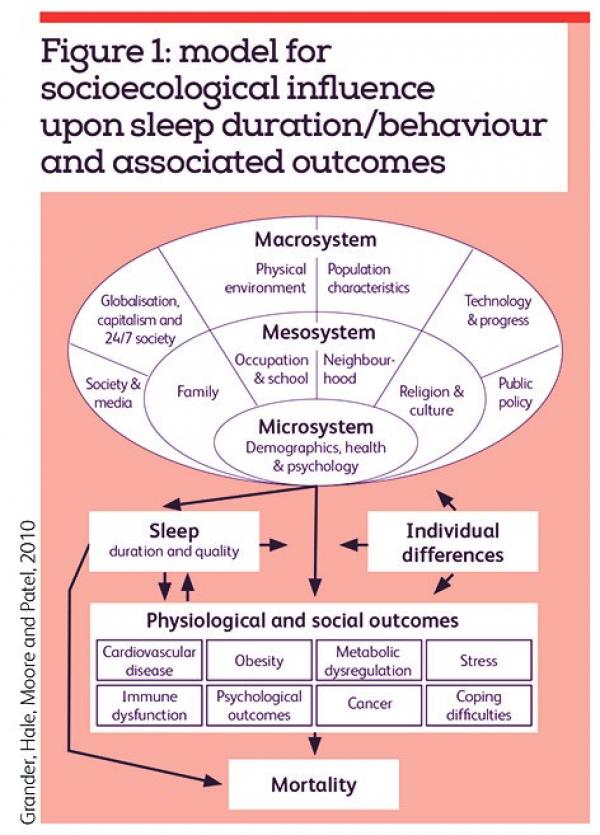

An American Academy of Sleep Medicine joint consensus statement reported that adults who sleep less than seven hours report poor general health, increased risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, mental health disorders and upper respiratory infection. Pain, cardiovascular, mental health and mortality have a ‘U’ shaped relationship with sleep. Seven to eight hours of sleep is associated with reduced risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and pain; and sleeping less than five hours or more than nine hours is associated with increased risk, as long hours of sleep are fragmented with less deep sleep and more time in REM sleep. Although there are genetic influences on sleep, environmental factors, such as occupational duties, commuting time, family responsibilities and social life can also affect sleep (Watson et al, 2015). To understand the biopsychosocial aspects please refer to figure 1 (Grander et al, 2010).

From a pyschoneuroimmunobiology perspective, Irwin (2016) describes how sleep influences the two primary effector systems, the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis and the sympathetic nervous system, which in turn regulate immune responses. This neuro-hormonal axis is also associated with chronic pain, fibromyalgia, stress, severe post-operative pain in disc surgeries, mental health and other immunological wellbeing.

Key practice points

- Sleep is a complex physiological process for recuperation, healing and normal functioning of the body and mind.

- Long-term sleep disturbance is associated with cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, obesity, mental health, infectious diseases and pain.

- Cardiovascular disease, diabetes and pain have a U-shaped relationship with sleep and lower risk noted in people sleeping seven to eight hours.

- Understanding the sleep disturbance is complex and related to several individual, environmental and social factors

Authors: Narender Nalajala is consultant physiotherapist and Laura Gutting is advance practice physiotherapist at Ashford and St Peter’s Hospital NHS Trust

Number of subscribers: 4